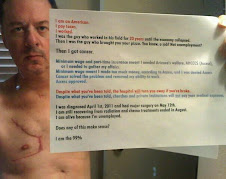

Occupy protestors in Long Beach, California spend a late night in October with Uno and banter. Credit: Quinn Norton/Wired

LONG BEACH, Calif. — At 10 p.m. every night, the Long Beach occupation moves off the lawn of Lincoln Park, packs up their infrastructure (they aren’t allowed to have tents), and moves onto the sidewalk to sleep for the night. At 6:00 a.m., the police return to the park in the center of the city, wake them up and herd the protesters back on to the lawn before the morning’s foot traffic arrives along the downtown street.

There are often several people who stay up through the night, usually talking about the movement to protest an economy that’s increasingly left the mainstream behind. One person who’s there, up, every night, is Nate. He’s a peacekeeper, and looks after the crowd, sleeping about four hours a day. He’s a skater, easy-going, Irish and proud of it.

He’s also a vet, and he’s written “Occupy the World” on the bottom of his skateboard.

“Hello!” he said brightly, into my recorder. “I’m currently an unemployed and unhoused vet, 21 years old, and I’m occupying Long Beach here at Lincoln Park.”

“Every night I will stay up and make sure that nobody takes any of the stuff from any of the occupiers that happen to be here, whether they’re just occupying for the night or staying for the long haul,” Nate said. “Make sure everyone gets their water, make sure everyone is taken care of, make sure there’s nothing sketchy. Just the general safety of the area. I want to create a sense of peace here.”

Nate, who declined to give his last name, explains how he de-escalates conflicts, mainly with the homeless; secures the area; talks to the occupiers and sometimes hands out blankets.

While he stands at less than five-and-a-half feet tall, he has a soldier’s physique and a physical and psychological confidence that makes the place feel safe.

While being part of a movement might sound exciting, in practice, occupations are often boring.

Last Thursday, a night I spent in the encampment, eight occupiers, all in their early 20s, gathered around a folding table pulled from under the tarp protecting the occupation’s belongings. They played Uno until dawn.

They talked and laughed, and look like nothing so much as a bunch of friends staying up too late in a dormitory common room.

The landscape of each occupation is defined by careful negotiations between that city’s occupiers and the police — sometimes day-by-day, sometimes by the hour. The police represent many things: local customs, their own law enforcement culture, the laws of the municipality and the attitudes of the municipality’s leaders at any given time. Most occupations are tense, and many are under constant threat of eviction, and the tension wears down the occupiers.

Jonah Quest, 17, chose to get arrested in OccupyLB’s only act of civil disobedience thus far. Quest is a clean-cut kid with tired eyes, decked out in a red cable-knit sweater pulled over a smudged collared shirt with one white collar sticking out.

Jonah Quest, 17, chose to get arrested in OccupyLB’s only act of civil disobedience thus far. Quest is a clean-cut kid with tired eyes, decked out in a red cable-knit sweater pulled over a smudged collared shirt with one white collar sticking out.

“It’s been difficult,” he said. “I’ve been juggling school and my mom, but I’ve been working it.”

How did his parents feel about him being arrested? “They weren’t too keen on it at first, but they’re okay with it now,” Quest said.

He goes on to talk about education reform, Kant and the categorical imperative, and Malcolm Gladwell’s book, Outliers. He doesn’t speak about his specific needs and fears, but about morality of the system.

“A lot of people can’t find jobs,” Quest said. “A lot of people have found their jobs taken away by unemployed 40 year olds.”

At night at Lincoln Park, I’m surrounded by the quiet chatter of a sidewalk crowd of about 50 people. The street is bathed in the warm municipal street lamp light; but the crowd is drowned in much harsher floodlights.

Three industrial flood lamps, two diesel-powered and one solar-powered, have been trained on Long Beach’s occupation. The occupiers told me the police said it’s for safety. But Tammara Phillips, 44, one of the occupation’s police liaisons, says Deputy Chief Lune went further in a meeting with city staff, telling them the lights were there to make recording the occupiers easier.

The occupation has quickly become familiar with the creature the city becomes at night.

Part of local homeless population slept in Lincoln Park before the occupation showed up, and some of them have joined the movement. Others sleep next to the protest, and the problems of the chronically homeless sometimes spill over into the lives of the occupiers. The untreated mentally ill yell a lot, and even push people occasionally. One of the homeless men, who has joined the occupation, thinks of the occupiers as “playing homeless” and worries about police later retaliating against the homeless who joined the group, if and when the occupation leaves.

The night had its other characters as well; three slouching men with suspicious eyes who several occupiers believed to be drug dealers showed up, followed quickly by police no one seemed to have called. The men mixed in, but not well, with the occupiers. They darted like lithe predators, but the police boxed them up, pushing deeper in the closed park. The police had a bored and bland hostility to the new arrivals, as if they were familiar with them, or at least familiar with their type. The police cleared them out, and left again.

Most of the occupiers, even the ones without a home, don’t face the same problems the chronically homeless do, but under local ordinance, they are treated very much like them. Many occupiers would tell me over the course of the evening that Long Beach has “made homelessness de facto illegal,” in exactly those words.

“We’ve gotten a real eye-opener about how the homeless in our community are treated,” Phillips said.

Even in Southern California, there’s a struggle to keep warm at night. There’s talk of winter here, and at every occupation I’ve visited. No one is sure how to keep this going through even the California winter, much less the Eastern winter everyone knows is headed for the heart of the occupation in New York City. Many occupiers fear the weather will cause the movement to fade as people head for inside warmth, but each of them talk of ways to stay.

The occupiers struggle to sleep. They struggle with morale. They struggle with the health and mental wellness of a growing homeless population that sees them as a resource, and while the homeless support the encampment, they weigh heavily on its resources as well.

But if OccupyLB survives, it will probably be on the back of Nate.

Nate talked about serving in Afghanistan twice, after getting on the plane to basic training on his 17th birthday. He’s proud of being a soldier, and what he learned in the Army, but still he darkened when he talked about his service:

For me (the occupation is) about helping my brothers and sisters … The government lied to me when it told me that’s what I’d be doing over there (in Afghanistan). Instead I was just killing people in their homes, and taking their land from them like was done here so many years ago, happening yet again.

I was only 17, I was very naive and I bought the recruiting speech, hook, line, and sinker. It’s really not so cut and dry, and they use this grand illusion of patriotism and glory to lure young men into the service to do their duty, when really it’s just a privatized militarized force going and colonizing other people’s lands and killing the civilians there.

If the occupation survives the winter, it will be down to people like Nate, veterans and other survivors who have trained or otherwise acquired the skills to endure conditions which most can’t or won’t. Fortunately for the occupation, there are a lot of unemployed vets in America.

Images: Quinn Norton/Wired.com

This post is part of a special series from Quinn Norton, who is embedding with Occupy protestors and going beyond the headlines with Anonymous for Wired.com. For an introduction to the series, read Quinn’s description of the project.

No comments:

Post a Comment