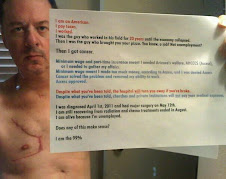

Axel Koester/Corbis

Many people benefited from projects like this one near Los Angeles but had no idea that it was part of the Obama stimulus.

By DAVID FIRESTONE

Published: September 15, 2012

Republicans howled on Thursday when the Federal Reserve, at long last,

took steps to energize the economy. Some were furious at the thought

that even a little economic boost might work to benefit President Obama

just before an election. “It is going to sow some growth in the economy,”

said Raul Labrador, a freshman Tea Party congressman from Idaho, “and

the Obama administration is going to claim credit.”

Mr. Labrador needn’t worry about that. The president is no more likely

to get credit for the Fed’s action — for which he was not responsible —

than he gets for the transformative law for which he was fully

responsible: the 2009 stimulus, which fundamentally turned around the

nation’s economy and its prospects for growth, and yet has disappeared

from the political conversation.

The reputation of the stimulus is meticulously restored from shabby to skillful in Michael Grunwald’s important new book, “The New New Deal.”

His findings will come as a jolt to those who think the law “failed,”

the typical Republican assessment, or was too small and sloppy to have

any effect.

On the most basic level, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act is

responsible for saving and creating 2.5 million jobs. The majority of

economists agree that it helped the economy grow by as much as 3.8

percent, and kept the unemployment rate from reaching 12 percent.

The stimulus is the reason, in fact, that most Americans are better off

than they were four years ago, when the economy was in serious danger of

shutting down.

But the stimulus did far more than stimulate: it protected the most vulnerable from the recession’s heavy winds. Of the act’s $840 billion final cost,

$1.5 billion went to rent subsidies and emergency housing that kept 1.2

million people under roofs. (That’s why the recession didn’t produce

rampant homelessness.) It increased spending on food stamps,

unemployment benefits and Medicaid, keeping at least seven million

Americans from falling below the poverty line.

And as Mr. Grunwald shows, it made crucial investments in neglected

economic sectors that are likely to pay off for decades. It jump-started

the switch to electronic medical records, which will largely end the

use of paper records by 2015. It poured more than $1 billion into

comparative-effectiveness research on pharmaceuticals. It extended

broadband Internet to thousands of rural communities. And it spent $90

billion on a huge variety of wind, solar and other clean energy projects

that revived the industry. Republicans, of course, only want to talk

about Solyndra, but most of the green investments have been quite

successful, and renewable power output has doubled.

Americans don’t know most of this, and not just because Mitt Romney and

his party denigrate the law as a boondoggle every five minutes.

Democrats, so battered by the transformation of “stimulus” into a

synonym for waste and fraud (of which there was little), have stopped

using the word. Only four speakers at the Democratic convention even

mentioned the recovery act, none using the word stimulus.

Mr. Obama himself didn’t bring it up at all. One of the biggest

accomplishments of his first term — a clear illustration of the

beneficial use of government power, in a law 50 percent larger (in

constant dollars) than the original New Deal — and its author doesn’t

even mention it in his most widely heard re-election speech. Such is the power of Republican misinformation, and Democratic timidity.

Mr. Grunwald argues that the recovery act was not timid, but the

administration’s effort to sell it to the voters was muddled and

ineffective. Not only did White House economists famously overestimate

its impact on the jobless rate, handing Mr. Romney a favorite talking

point, but the administration seemed to feel the benefits would simply

be obvious. Mr. Obama, too cool to appear in an endless stream of photos

with a shovel and hard hat, didn’t slap his name on public works

projects in the self-promoting way of mayors and governors.

How many New Yorkers know that the stimulus is helping to pay for the

Second Avenue subway, or the project to link the Long Island Rail Road

to Grand Central? Almost every American worker received a tax cut from

the act, but only about 10 percent of them noticed it in their

paychecks. White House economists had rejected the idea of distributing

the tax cuts as flashy rebate checks, because people were more likely to

spend the money (and help the economy) if they didn’t notice it. Good

economics, perhaps, but terrible politics.

From the beginning, for purely political reasons, Republicans were

determined to oppose the bill, using silly but tiny expenditures to

discredit the whole thing. Even the moderate Republican senators who

helped push the bill past a filibuster had refused to let it grow past

$800 billion, and prevented it from paying for school construction.

No comments:

Post a Comment