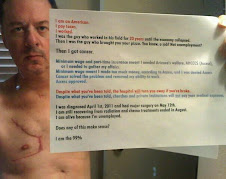

A lot of People don`t know that my New Husband Roy has a fake eye....he is legally blind....he cannot get a drivers license, so I am his driver whenever he needs to go anywhere....however nothing stops him and you would Never Know.....here is an interesting article below about him & his eye.

He was Blind Completely for almost 2 yrs- had to go to the Braille Institute & use a cane to go about life. He regained sight in one eye- but the other Eye is gone. His one good eye is not good either- has to have a lot of work, fancy contact lenses & eye drops to see.

The eyes have it

Tustin ocularist uses his art training to craft as-real-as-life replacements.

By CHRIS KNAP

The Orange County Register

http://www.ocregist er.com/ocregiste r/news/atoz/ article_710953. php

TUSTIN – John Kennedy pries out Ronald Luse's right eye with what looks like a screwdriver and presses it firmly against a whirring grinder.

Luse is cheerful.

"It falls out about once a year, but it's usually my fault," he reports.

Kennedy reinstalls the eye and appraises it like a jeweler.

"I think we could improve it a little," Kennedy says.

"My grandkids have a field day trying to tell which one is my real eye," Luse says. "I think it's perfect."

Kennedy, 53, smiles and sits back on his stool.

The patients who come to Eye Design Ocular Prosthetics have been through some of the most frightening diseases the mind can conceive.

Take Roy Hetherington, 36, whose eyes were attacked by the autoimmune disease iritis. His left eye withered and died, then shrank in his head.

Or Brenda Storz, 35, who lost her right eye to retino blastoma, a voracious cancer, when she was just 2.

And now Luse, 70, whose eyeball shriveled and dark ened two years ago after a stroke and glaucoma.

"It died on me," Luse says matter-of-factly. "It was very, very painful. If they hadn't taken it out I would have dug it out myself."

These are horror stories to curl the hair of most people, but Kennedy's patients are mostly past the pain. What they aren't past is the social stigma linked with disfigurement, the jerk of the head when someone notices there's something more than a little odd about their eyeballs.

"This eye is not for me. This eye is for how the rest of the world perceives me," says Storz.

That's where Kennedy comes in, a meticulous craftsman with an easy manner and an encyclopedic eye for color. He's an expert in the obscure science of reopening the window to the soul.

One of just 200 ocularists in North America, Kennedy has made eyes for babies born without, for war veterans who sacrificed an orb for honor; for people of all ages attacked by accident or disease.

When Hetherington came to Kennedy, he was still stinging from a comment by a former boss bothered by his wandering, shrunken eye.

"Can't you get that fixed?" the man demanded.

Turned out he could, although the first version, by another ocularist, bulged strangely and hardly matched his original hazel.

Kennedy made a perfect match, colored by sight and paintbrush, and today it's impossible to say which eye might not be real.

Still, Kennedy's not satisfied. One eye opening appears slightly wider. He removes the orb - turns out the tool is actually a suction cup - and attacks it with a grinder, removing material along the edge to relieve pressure on the eyelid. Reinserted, the eyes match.

Hetherington is ebullient, reporting how much his girlfriend, his family, his co-workers like his new eye.

"We live in a visual society. We are very into appearances. The first thing you look at is the face, and flaws stand out right away," Hetherington says. "When you lose an eye, it takes away part of your confidence. Once you get that part restored, you can almost forget that you lost it in the first place."

Kennedy says many of his patients share that feeling.

"I approach this as an art, but it's also real rewarding. I am helping people feel complete again."

THE PAINTER

Kennedy opens a tattered portfolio and removes 20 years' worth of watercolors.

He once pursued art as a career, but came to believe it wasn't practical.

In 1974, he disappointed his art teachers at Orange Coast College by switching to dental technology, where he would learn to make dentures.

"I could still sculpt and paint and get paid for it."

He took a job in the dental school at UC San Francisco, and became known as a master at creating lifelike dentures.

It was a good job, but something was missing. Kennedy wandered in the woods near Half Moon Bay, rendering landscapes in gauzy colors.

Rubbing shoulders with the dentists, Kennedy realized what it was. They were working with patients, while he was toiling alone in the lab.

"I wanted to be more directly involved with people."

In 1990 he quit his job and took an apprenticeship at a VA hospital in Delaware, where he learned to make ocular prosthetics.

He absorbed the new training quickly, standing out for his ability to relate to people and to match their real eyes.

His watercolors from this period are more vivid, infused with brighter colors, subtle reflections, and life. Kennedy had found his calling.

In 1997 he returned to Orange County to start his own shop, struggling to set up an ocular practice from scratch. In those first years, he made custom dentures to help pay the bills.

"The day I stopped doing dentures, that was a great day," he recalls.

THE MECHANIC

While waiting for Brenda Storz, who is driving from Thousand Oaks, Kennedy pages through an old British sports car catalog, looking for parts for his MGA.

Finally Storz arrives, a fashion-model- tall mother of two with emerald-green eyes.

For 20 years Storz wore a "stock eye," an off-the-shelf model fitted by an ophthalmologist. It was a little smaller, a little off in color, clearly not the same as her real eye. She compensated by being twice as outgoing. After a two-year fiasco with another ocularist, who kept promising high-tech solutions but delivering nothing, Storz was careful about choosing a new ocularist.

Was his approach primarily artistic or scientific, she asked Kennedy? (He said artistic.)

How long would it take him to make the eye? (One day.)

You might think that modern eye prosthetics are some sort of high-tech science, miracle polymers matched by computer chromatograph.

Not so - and perhaps that's a good thing. Kennedy's not much for computers. He makes eyes using technology developed by the Army in the 1940s, when the supply of German glass eyes dried up.

He make a gel impression of the eye socket, a wax model of the eye, then a plaster cast of the model. The artificial eye is cast out of methyl methacrylate, an epoxy-like plastic.

Now comes the most intense part: Staring at Storz, he colors the sclera, iris and pupil, scratching his brush in dried pigment and simulating veins with scraps of thread.

Essentially, Kennedy has painted a portrait of her good eye on the plastic model.

He tops the colors with another layer of plastic, presses the model in a vise and cooks it at 212 degrees, then polishes it with pumice. Now Storz has two emerald orbs, an overwhelming change.

"You've stepped in a really intimate place with people like that," Kennedy says.

"It's a huge emotional impact when they look in the mirror and they're whole again."

Contact the writer: (714) 796-2240 or cknap@ocregister. com

July 3, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

never noticed, or even knew Roy was blind! My grandfather was born blind in one eye and I can tell, he has a fake eye. But with Roy, I never guess! Way to go Roy. I am so glad he doesn't let being blind stop him. He shouldn't. He is a good man, with a lot of life!

Post a Comment